Governing ID:

India’s Unique Identity Programme

This is the second in a series of case studies, using our evaluation framework for the governance of digital identity systems. These case studies, which analyse identity programmes and their uses, illustrate how our evaluation framework may be adapted to study instances of digital identity across different regions and contexts. This case study looks at the Unique Identity scheme in India.

The Unique Identity (UID) scheme or Aadhaar is intended as a foundational identity system that stores the demographic and biometric information of all residents in India and allows the Aadhaar number holder to establish their identity through authentication or offline verification (although no guidance has been further provided about how this mechanism will work).1 All the identity information is stored in a centralised database, the Central Identities Data Repository (“CIDR”) and can be “seeded” 2 with other existing databases.

Rule of Law Tests

Legislative Mandate

Is the project backed by a validly enacted law?

The Union of India issued a Notification dated 28.01.2009, constituting the Unique Identification Authority of India (“UIDAI”) for the purpose of implementing the Unique Identity (UID) scheme. The UID scheme envisaged the issuance of a digital ID, “Aadhaar,” through the creation of a UID database. The first Aadhaar number was in 2010, without any statutory backing. The government continued to issue Aadhaar numbers solely on the basis of the Executive Notification, till the passage of the Aadhaar Act in 2016.

During the pendency of several legal challenges filed in the Supreme Court of India, the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016 (“Aadhaar Act”) was introduced as a “Money Bill” under Article 110 of the Constitution of India and passed.3 All these challenges were heard together by the Indian Supreme Court in K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India, (2019) 1 SCC 1 (“Aadhaar judgment” ), which by a majority of 4:1 upheld the constitutionality of the Act, while striking down/reading down certain sections. The Supreme Court also upheld Section 59 of the Act, thus validating the Aadhaar project (i.e. the enrolment/storage/use of Aadhaar) from 2009 till 2016, prior to the passage of the Aadhaar Act.4

In 2019, the President of India promulgated the Aadhaar and Other Laws (Amendment) Ordinance, 2019, (Amendment Act). This Ordinance has been challenged before the Supreme Court in S.G. Vombatkere v Union of India.5 Although the Supreme Court in the Aadhaar judgment had upheld the passage of the Aadhaar Act as a Money Bill,6 the issue has been thrown open again. In a recent decision in Rojer Mathew v South India Bank Ltd, (2019) SCC Online SC 1456, the Supreme Court raised questions over the majority’s interpretation of Article 110(1) of the Constitution, noting a “potential conflict” with judgments of the coordinate Bench. Consequently, the Court referred the issues of Money Bill to a larger bench. Thus, a re-examination of the Money Bill issue, pertaining to the Aadhaar Act, will likely be reopened.

While there is a law backing the ID system, the validity of the law is likely to be legally examined.

Legitimate Aim

Does the law have a ‘legitimate aim?’ Are all purposes flowing from a ‘legitimate aim’ identified in the valid law?

The primary requirement of the legitimate aim test is that the actions in questions must respond to a pressing social need, and should not operate in a manner that discriminates on the basis of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. The objectives laid down in the Aadhaar Act satisfy the legitimate aim test.7 Section 2(k) of the Act, defining “demographic information” expressly excludes the collection of information regarding race, religion, caste, tribe, ethnicity, language, records of entitlement, income or medical history. The Supreme Court in the Aadhaar judgment held that the Aadhaar Act had a legitimate aim, relying primarily on Section 7 of the Act, while noting that it was “aimed at offering subsidies, benefits or services to the marginalised sections of the society for whom such welfare schemes have been formulated from time to time” and “the objective of the Act is to plug the leakages and ensure that the fruits of welfare schemes reach the targeted population, for whom such schemes are actually meant.” 8

Even though the law has a legitimate aim, it does not clearly define the purposes for which the ID system can be used.

Defining Actors and Purposes

Does the law governing the ID system clearly define all the actors that can use or are connected to it in any way?

The Aadhaar Act does not clearly define all the actors that can use or manage, or are connected to the Aadhaar database. The Amendment Act introduces the definition of “Aadhaar ecosystem” which includes enrolling agencies, Registrars, requesting entities, offline verification-seeking entities and any other entity or group of entities as may be specified by regulations.9 These actors, apart from the Aadhaar number holders themselves, can use/manage or are connected to the CIDR. However, no ensuing amendment has been made to the existing Aadhaar Regulations to give any further details about the actors, especially the offline verification seeking entities, in the Aadhaar ecosystem.

Other actors can also use the ID system for the process of organic/inorganic seeding described above. The government has in the past notified more than 250 schemes, including for Public Distribution Systems and for pension, through over 130 notifications passed under Section 7 of the Act, to require Aadhaar for authentication.10

Several actors are not clearly defined in the Aadhaar Act or the supporting regulations itself.

Regulating Private Actors

Is the use of the ID system by private actors adequately regulated?

Section 57 of the original Aadhaar Act permitted private sector use of Aadhaar. However, a part of Section 57, which enabled private actors to seek authentication on the basis of a contract, was struck down by the Supreme Court in the Aadhaar judgment since it enabled commercial exploitation of an individual biometric and demographic information by these entities and violated the privacy of the Aadhaar number holders.11 There has been a lot of debate about the true meaning of the Court’s ruling and the status of private entities in the Aadhaar ecosystem. One view was that after the partial striking down of Section 57, private actors were not permitted to use the Aadhaar infrastructure even as requesting entities, even under a voluntary contract. Others argued that the wide definition of “requesting entity” 12 and the mandate given to the UIDAI to perform authentication of the Aadhaar number submitted by any requesting entity13 meant that the private sector could continue to use Aadhaar through this route.

In 2019, through an amendment, the government omitted Section 57, but effectively restored private sector use of Aadhaar through other amendments.14 The Telegraph Act was further amended by introduction Section 4(3) clarifying that a licensee under the Telegraph Act can identify its customer/user by authentication or offline verification under the Aadhaar Act (based on their consent), apart from existing methods such as identification through passports. Similarly, Section 11A was inserted in the PMLA Act, 2002 authorising every reporting entity to verify the identity of its clients and the beneficial owner through Aadhaar authentication or offline verification, if they choose this method.

The amendments to the Aadhaar Act, that have re-introduced private actors into the Aadhaar ecosystem, are now the subject matter of a judicial challenge.

Data Specification

Does the law clearly define the nature of data that will be collected?

The Aadhaar Act provides for the collection of biometric information and demographic information. Biometric information has been defined as meaning “photograph, finger print, Iris scan, or such other biological attributes of an individual as may be specified by regulations.” 15 “Core biometric information” 16 means fingerprint, iris scan, or such other biological attribute of an individual as may be specified by regulations. Demographic information has been defined as including “information relating to the name, date of birth, address and other relevant information of an individual, as may be specified by regulations for the purpose of issuing an Aadhaar number, but shall not include race, religion, caste, tribe, ethnicity, language, records of entitlement, income or medical history.” 17

Both biometric and demographic information, although defined, leave room for the State to prescribe further types of information that can be collected.

User Notification

Does the ID system provide adequate user notification mechanisms?

There are no requirements for notification to the individuals concerned in the case of access by third parties. There are no provisions in place to provide notifications in case of unauthorised access within a reasonably practicable period of becoming aware of such breach.

There is no user notification provision either for breaches or for access by third parties.

User Rights

Do individuals have rights to access, confirmation, correction and opt out?

The Aadhaar Act denies individuals the right to access their own core biometric information stored in the CIDR. Further, the Enrolment Regulations state that the Aadhaar number holder has a “right to access information,” with the procedure for making such requests for access provided in Schedule I. However, the schedule only provides for right to access identity information aside from core biometrics. Thus, despite cross-citing each other, no procedure is laid down. The Authentication Regulations gives the Aadhaar number holder the right to access the authentication transactions logs during the two year period for which they are maintained. Regulation 28(1) grants the right to access one’s authentication records “within the period of retention of such records before they are archived,” which as per Regulation 27(1) is 6 months.

The right of correction is recognised in the form of the right to “update” resident information under Section 31(1) of the Act read with Chapter IV of the Enrolment Regulations.

The Aadhaar Act does not provide any specific opt out option. The UIDAI has clarified that the only option available with residents is the option of permanently locking their biometrics and only temporarily unlocking it when needed for biometric authentication as per Regulation 11 of the Aadhaar (Authentication) Regulations.18 In the context of children, the Supreme Court clarified that the enrolment of children would be done under the consent of their parents/guardians, and on attaining the age of majority (18 years), such children would be given the right to exit Aadhaar, if they so choose.19 This has now been given statutory recognition vide the Aadhaar Amendment Act.20

However, this opt out is partially notional since both (i) adults who pay taxes, and who have to link their PAN card with the Aadhaar number; and (ii) adults who receive subsidies, benefits, or services require an Aadhaar number. Hence, for a majority of adults, the right to opt out can only exist between 18 years and the time they start paying taxes or receiving benefits. The Aadhaar Act is silent on the deletion of data from the Central Identities Data Repository once the opt out takes place.

While the Aadhaar Act introduces some user rights, there are limited rights to access and opt-out provided.

Redressal Mechanisms

Does the law provide for adequate redressal mechanisms against actors who use the Digital ID and govern its use?

Prior to the amendment, the Aadhaar (Enrolment and Update) Regulations prescribed a weak and ineffective grievance redressal system, through the mechanism of a “contact centre.” The Aadhaar Amendment Act introduced a new chapter dealing with civil penalties including constituting an Adjudicating Authority and an Appellate Tribunal. However, it is relevant to note that Regulation 4(3) of Sharing Regulations states that private requesting entities “may” share the authentication logs of an Aadhaar number holder with them upon their request, with no recourse to the Aadhaar number holder if such a request is denied.

The Aadhaar Act originally permitted the disclosure of identity information or authentication records of individuals, pursuant to a judicial order nor inferior to that of a District judge, after hearing the UIDAI only. No ex ante or ex post hearing was given to the concerned Aadhaar number holder. The Supreme Court read this down to clarify that an individual, whose information is sought to be released, shall be afforded an opportunity of hearing, and a right to challenge the order passed.21 Pursuant to the amendment, it is now required that the order be made by a Judge of a High Court, after hearing the UIDAI and the concerned person; and that even then, core biometric information could not be disclosed under the section.

The Aadhaar Act clarifies that an inquiry for adjudicating a civil penalty can be initiated only on a complaint made by the UIDAI, although the entity in the Aadhaar ecosystem against whom a complaint had been made, will be provided with a right to be heard. The Aadhaar Act originally provided that the cognizance of an offence could only be taken by a criminal court on the complaint made by the UIDAI or any officer or person authorised by it. The Supreme Court held that a “suitable amendment” was needed “to include the provision for filing of such a complaint by an individual/victim as well whose right is violated.” 22 It was amended to permit an individual or (aggrieved) Aadhaar number holder to make a complaint for offences punishable under Sections 34-37, 40-41. Thus, even at present, only the UIDAI is competent to initiate criminal action for other offences.

The Enrolment Regulations empowers the UIDAI to omit or deactivate an Aadhaar number. Although the Aadhaar Act and Enrolment Regulations23 provide for deactivation and omission of Aadhaar numbers, no provision is made for providing a hearing prior to such deactivation and omission. The individual is informed only after the decision has been made.

The Aadhaar Act does not provide any remedies, including appeal or compensation, for persons who have been wrongfully suffered exclusion on account of Aadhaar related authentication failures.

Accountability

Is there an independent and adequate regulatory mechanism to ensure accountability of the administrator of the ID system?

The UIDAI suffers from a conflict of interest since it serves both as an administrator (i.e. it collects and maintains the demographic and biometric information of all residents; it oversees the authentication and offline verification process) and a regulator (it licenses and regulates various entities in the Aadhaar ecosystem; notifies Regulations; is in charge of the contact centre grievance redressal mechanism, and has the power to issue binding directions to any entity in the Aadhaar ecosystem). These roles can often be in conflict with each other. There is no independent agency tasked with regulating the conduct of UIDAI, nor is there any data protection law currently in place.

The only source of accountability seems to be in the form of a financial audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General.24 There is no accountability for security breaches nor is any performance audit carried out at the end of the year.

However, pursuant to the amendment, the UIDAI has been empowered to appoint its officers and employees, without requiring the Central Government’s approval, and the salaries and allowances and other terms and conditions of service of such officers/employees do not require the approval of the Central Government.25 This has improved the independence of the UIDAI from the government.

The dual role of administrator and regulator performed by the UIDAI creates a clear conflict of interest.

Mission Creep

Does the governing law explicitly specify the proposed purposes of the ID system?

The proposed purpose for the digital ID (Aadhaar) has been specified in the Act – mainly, the use of Aadhaar for establishing the identity of an individual as a condition for receipt of a subsidy, benefit or service for which the expenditure has been incurred from the Consolidated Fund of India or the State. The powers and functions of the UIDAI, including for “specifying the manner of use of Aadhaar numbers for the purposes of providing or availing of various subsidies, benefits, services and other purposes for which Aadhaar numbers may be used” 26 has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to mean that the “other purposes” must have its relation to subsidies, benefits and services mentioned in Section 7 and be confined only to that purpose i.e. scheme of targeted delivery for giving any grant, relief, etc. when it is chargeable to the Consolidated Fund of India.27 Other purposes for Aadhaar have been expressly mandated by other statutes.28

Other voluntary purposes for which Aadhaar may be used are not clearly specified, nor is it made clear which are the categories of actors who may make use of it.

The Aadhaar Act, post amendment, is silent on voluntary uses for Aadhaar, stating only that an entity may be allowed to perform authentication if the UIDAI is satisfied that the requesting entity is “seeking authentication for such purpose, as the Central Government in consultation with UIDAI, and in the interest of State, may prescribe.” It is relevant to note that it has been made clear that the purpose has to be informed in writing to the Aadhaar number holder by a requesting entity/offline verification seeking entity at the time of submitting the identity information.29

There are no provisions in place or practices envisaged to have a process for determining the appropriateness or legitimacy of new uses and purposes. In the past, the purpose for the use of Aadhaar was made clear through various notifications issued by the Central or State Government that mandated Aadhaar authentication for the receipt of a certain specific benefit, subsidy, or service such as social security pension or PDS (Public Distribution System).30

Rights based Tests

Necessary and Proportionate

Are principles of data minimisation followed in the collection, use, and retention of personal data?

The Supreme Court held that principles of data minimisation have been “largely followed.” In reaching its conclusion, the Court relied on three factors – (i) the collection of photographs and demographic information, did not raise any reasonable expectation of privacy, especially given the prohibition of collection of certain specified types of demographic information under Section 2(k); (ii) minimal biometric data in the form of iris and fingerprints is collected during enrolment, and no purpose, location or details of the authentication transactions are collected; and (iii) Section 32(3) of the Act and the proviso to Regulation 26 of the Authentication Regulations specifically prohibited the UIDAI from collecting, storing or maintaining, either directly or indirectly any information about the purpose of authentication.31

However, there were several practices, which were held as violative of the data minimisation principle:

- The provision permitting the authentication records to be archived for a period of five years was held to be bad in law. Authentication records are not to be kept beyond a period of six months, as stipulated in Regulation 27(1) of the Authentication Regulations.

- The storage and maintenance of metadata relating to the authentication transaction by the UIDAI under the Authentication Regulations was impermissible in its present form and needed a suitable amendment.

- Section 33(2), which gave a carte blanche to the State to access/use/disclose identity information of individuals, including their core biometric information, “in the interest of “national security” based simply on the direction of officer not below the rank of Joint Secretary was struck down in its present form. Given the importance of the power, the Court noted, an officer higher than the rank of a Joint Secretary should be empowered; and to avoid misuse, a Judicial Officer, preferably a sitting High Court judge should also be associated to arrive at the conclusion that the disclosure was in the interest of national security.32 Vide the amendment, the power was entrusted with the Secretary (instead of the Joint Secretary), but no judicial supervision/oversight has been provided for.33

There is a need for better data minimisation practices with regard to core biometric information and storage of metadata.

Access to Data

Does the law specify access that various private and public actors have to personal data?

Apart from what has already been stated, certain other sections are required to be noticed. Section 29(3) of the Aadhaar Act provides that no identity information with a requesting entity shall be used for any purpose, other than the purposes informed in writing to the individual at the time of submitting their information. Section 29(4) of the Aadhaar Act stated that an Aadhaar number or core biometric information could be published in a manner “as may be specified by regulations.” This was upheld on the ground that Aadhaar (Sharing of Information) Regulations, 2016, as of now, do not contain any such provision.34 Pursuant to the amendment, the words “core biometric information” in section 29(4) were substituted by “demographic information or photograph.”

The law specifies the level of access different actors have to personal data.

Exclusions due to Design Flaws

Is the use of digital ID in identification and authentication exclusionary?

The digital ID, Aadhaar, is premised on biometric and demographic identification. It is well documented in the context of biometrics, “human recognition systems are inherently probabilistic, and hence inherently fallible. The chance of error can be made small but not eliminated.” 35 In a paper, Hans Verghese Mathews reported that given current population, UIDAI should expect 1 in every 121 persons to be a “duplicand,” i.e. giving a false positive for biometric identification; and by the time the population increases to 1.5 billion, 1 in every 97 persons is expected to be a duplicand.36

Aadhaar Proof of Concept studies have shown that less than 2% residents will not be able to successfully authenticate using biometric modalities such as fingerprints and/or iris,37 and will have to rely on exception handling processes. The Government admitted that there had been cases of exclusion caused due to unsuccessful authentication.38 UIDAI’s own Report on “Role of Biometric Technology in Aadhaar Enrolment” in 2012 acknowledged that the biometric accuracy after accounting for the biometric failure to enrol rate, false positive identification rate, and false negative identification rate, was 99.768% accuracy. For a population of over 119.22 crore enrolled in Aadhaar, this translates into roughly 27.65 lakh people who would be excluded from benefits linked to successful Aadhaar authentication. In Court too, the UIDAI has admitted slightly higher authentication failure rates have been observed for fingerprints for senior citizens above the age of 70.39

Apart from biometric identification, successful authentication is also dependent on a host of other external factors, such as correct Aadhaar-seeding, successful fingerprint recognition, mobile and wireless connectivity, electricity, functional POS machines and server capacity; as well as age, disability (e.g. leprosy), and class of work (e.g. manual labour). All these factors can contribute to exclusion.

Even when it works as intended, there are clear demonstrable exclusionary impacts of the ID system.

Exclusions due to Failure

Does failure of the ID system lead to exclusion?

The (i) probabilistic nature of biometric authentication (which gets exacerbated with age, class, manual labour, and disability), (ii) structural capacity constraints (such as poor internet and mobile access), (iii) machine errors (e.g. in the fingerprint recognition software), (iv) manual seeding errors (which requires the name, demographic information, and Aadhaar number to be correctly and identically recorded across databases) contributes to exclusion.

The Economic Survey of India 2016-17 reports that authentication failures have been as high as 49% in Jharkhand and 37% in Rajasthan, recognising that “failure to identify genuine beneficiaries results in exclusion error.” 40 Several reasons such as inadequate server and lease line capacity at data centres, poor mobile connectivity at POS shops, incorrect seeding of Aadhaar Numbers, and lack of proper training to operators have been identified for authentication failures.

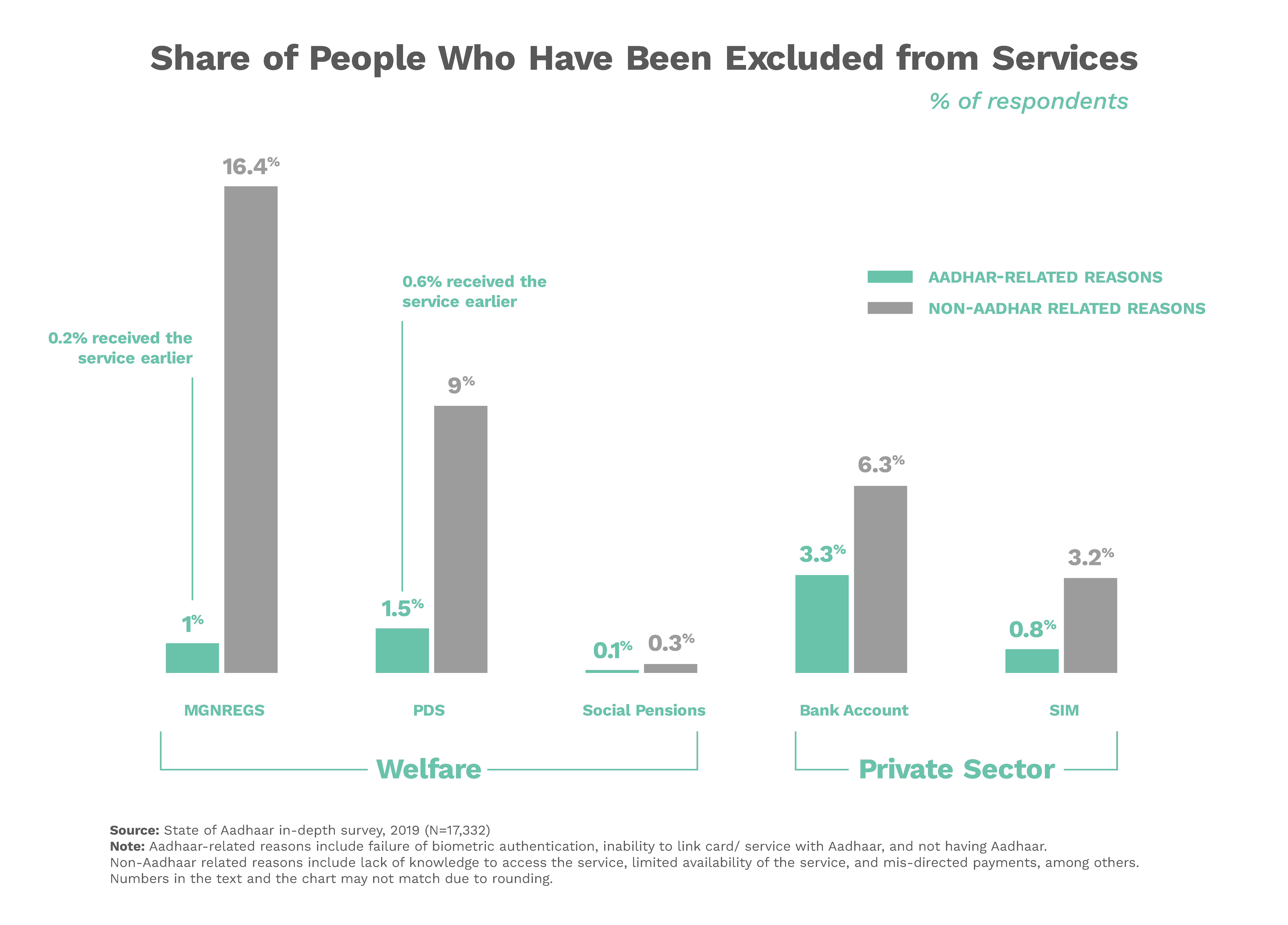

In a third party report, “State of Aadhaar – 2019,” 41 based on pulse survey of 1.47 lakh respondents and an in-depth survey of 19,209 respondents, it was found that 2.5% of all respondents experienced exclusion from a key welfare service — they could not access it at all. One-third of them (0.8%) previously had accessed the service. Non-Aadhaar related reasons contributed to exclusion from services for several times as many people (22% experienced exclusion for non-Aadhaar related reasons; 3.5% experienced exclusion for non-Aadhaar related reasons from a service they had earlier received).

The above graph clarifies that “Aadhaar-related reasons” for exclusion included failure of biometric authentication, inability to link card/service with Aadhaar, and not having Aadhaar. “Non-Aadhaar related reasons” include lack of knowledge to access the service, limited availability of the service, and mis-directed payments among others. The Report also found that marginalised groups, such as homeless and third-gender people, are disproportionately represented among those who face Aadhaar-related exclusion from services, such that these two groups were nearly one-third as likely to have access to PDS rations without Aadhaar than with Aadhaar.42

Authentication errors, manual errors and capacity challenges pose significant difficulties, and they all could lead to high human costs of exclusions.

Risk based Tests

Risk Assessment

Is the ID system regulated taking into account its potential risks?

There does not seem to be an adequate consideration of risk based factors in the Aadhaar Act. In the Aadhaar judgment, the UIDAI admitted43 that (i) no UIDAI official verifies the correctness of documents offered at the stage of enrolment/updating (ii) no UIDAI official verifies whether the documents shown at the time of enrolment/updating are genuine or false (iii) UIDAI does not take any independent responsibility with respect to the correctness of the name, date of birth or address of the person enrolled; (iv) no independent verification is carried out about whether the person, at the time of enrolment, is an illegal immigrant or has been a resident in India for 182 days or more over the last 12 months (beyond self-certification). The use case does not take into account the potential risks of the underlying documents supporting Aadhaar can be false.

Mitigation strategies (described below) were employed many years after reports of failures emerged. It is also not clear how if the success of Aadhaar and biometric authentication depends on every person being correctly seeded in the CIDR, how authentication can correctly verify the identity of an individual using “offline” measures or through OTP-based authentication (that simply depends on a mobile phone number and/or email address).44

While some mitigation strategies have been adopted, the design and development of the ID system has not adequately adopted a risk assessment approach.

Privacy Risk Mitigation

Is there a national data protection law in place?

India does not currently have a data protection law.

However, the Personal Data Protection Bill is likely to be placed before the Indian Parliament in the Budget/Winter Session of 2020-21, having received sent to the Joint Parliamentary Committee.

Privacy by Design

Are there privacy by design systems that minimise the harms from data breach?

The UIDAI introduced the Virtual ID (VID), which is a temporary, revocable 16-digit random number mapped with the Aadhaar number. VID was meant to be used in lieu of Aadhaar number whenever authentication or e-KYC services are performed. Authentication may be performed using VID in a manner similar to using Aadhaar number. The UIDAI clarified that it was not possible to derive Aadhaar number from VID.45

The Aadhaar Amendment Act amended the definition of Aadhaar number under Section 2(a) of the Act to include, apart from the 12 digit identification number, “any alternative virtual identity” that had been generated under Section 3(4) of the Act. Section 3(4) clarified that the Aadhaar number included “any alternative virtual identity as an alternative to the actual Aadhaar number…” that was to be generated by the UIDAI in the manner specified by Regulations. However, till date, no Regulations have been notified by the UIDAI to elaborate on the procedure for generating an alternative virtual identity.

The UIDAI also introduced the concept of a UID Token, which is a 72 character alphanumeric string meant only for system usage. Under this system, the token would remain the same for an Aadhaar number for all authentication requests by a particular entity (AUA/Sub-AUA). However, for a particular Aadhaar number, different AUAs/sub-AUAs would have different UID tokens.

In recent past, there have been attempts to introduce privacy by design solutions, however, there are still in early stages of implementation.

Response to Risks

Is there a mitigation strategy in place in case of failure or breach of the ID system?

To reduce the risk of exclusion caused by the failure of the authentication of the ID system (Aadhaar), the Cabinet Secretariat had released an Office Memorandum46 detailing an “exception handing” mechanism. The Memorandum created the following mechanism for availing subsidies, benefits or services in cases where Aadhaar authentication fails —

- Departments and bank branches may make provisions for iris scanners along with fingerprint scanners wherever feasible;

- in cases of failure due to lack of connectivity, offline authentication systems such as QR code based coupons, mobile based OTP or TOTP may be explored; and

- in all cases where online authentication is not feasible, the benefit/service may be provided on the basis of possession of Aadhaar, after duly recording the transaction in a register, to be reviewed and audited periodically.

A proviso was also added to the Aadhaar Act which made it clear that in case of failure to authenticate due to illness, injury or infirmity owing to old age or otherwise or any technical or other reasons, the request entity shall provide such alternate and viable means of identification of the individual, as may be specified by regulations. However, no corresponding regulations have been notified.

The Aadhaar Amendment Act has further provided statutory backing to the idea of “offline verification,” 47 which is the process of verifying the identity of the Aadhaar number holder without authentication, through such offline modes, as will be specified by regulations. The Act also recognises the right of the Aadhaar number holder to establish their identity through offline verification. An Aadhaar number holder seeking offline verification cannot be subject to authentication.48

There is no mitigation strategy in place in case of a breach of the ID system, but other mitigating strategies for exclusionary impacts are being discussed and introduced.

Notes

| 1 | Section 4(3), Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016 [“Aadhaar Act”]. ↑ |

| 2 | Seeding is the process by which the Aadhaar number is introduced into various databases for identity verification. Inorganic seeding transpires when the database is automatically updated by the UIDAI using programming tools and algorithms, without the involvement of the Aadhaar number holder. See Aadhaar Seeding (2014) https://pdsportal.nic.in/Files/Aadhar%20seeding%20guidelines.pdf, 1. ↑ |

| 3 | The Act included a savings/validation provision, Section 59, which aimed at validating actions taken by the Central Government pursuant to Notification dated 28-1-2009 till the passing of the Act. The Aadhaar Act, including Section 59 was subsequently challenged vide W.P. (C) No. 797/16, titled S.G. Vombatkere and Anr. v. Union of India & Anr. ↑ |

| 4 | (2019) 1 SCC 1, paras 428, 431, 513.9. ↑ |

| 5 | After the Parliament came to session, the Aadhaar and Other Laws (Amendment) Law, 2019 [“Aadhaar Amendment Act”] was passed – without any public consultation – and was also challenged before the Supreme Court in S.G. Vombatkere v Union of India, W.P. (C) No. 1077/2019 [“S G Vombatkare” ]. The challenge pertains to expanding the use of Aadhaar to private entities, in the teeth of the Aadhaar judgment and the private surveillance architecture enabled by the Amendment Act. Notice was issued on this petition by the Supreme Court on 22.11.2019 and it was tagged with W.P.(C) No. 679/19. ↑ |

| 6 | S G Vombatkare, supra, para 515.5. ↑ |

| 7 | The objectives are “to provide for, as a good governance, efficient, transparent, and targeted delivery of subsidies, benefits and services, the expenditure for which is incurred from the Consolidated Fund of India, to individuals residing in India through assigning of unique identity numbers to such individuals and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.” ↑ |

| 8 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, paras 314, 373. ↑ |

| 9 | Section 2(aa), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 10 | See Reply to Lok Sabha Unstarred Qs No. 819 on 20.12.2017. ↑ |

| 11 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 513.8.3. ↑ |

| 12 | Section 2(u), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 13 | Section 8(1), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 14 | Section 4(4), Aadhaar Act was introduced to permit “an entity” to perform authentication, as long as (i) it was compliant with certain specified standards of privacy and security (which are yet to be specified) and (ii) it was permitted to offer authentication services by law or it was seeking authentication for certain prescribed purposes. ↑ |

| 15 | Section 2(g), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 16 | Section 2(j), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 17 | Section 2(k), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 18 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 60.5. ↑ |

| 19 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, paras 391-391.6. ↑ |

| 20 | Section 3A, Aadhaar Amendment Act. ↑ |

| 21 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 510.4.3, 513.5. ↑ |

| 22 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 513.7. ↑ |

| 23 | Section 23(2)(g), Aadhaar Act read with Regulations 27-30, Enrolment Regulation. ↑ |

| 24 | Daniel Solove, “10 Reasons Why Privacy Matters”, TeachPrivacy (blog), January 20 2014, https://teachprivacy.com/10-reasons-privacy-matters/. ↑ |

| 25 | Aadhaar judgment. ↑ |

| 26 | Aadhaar Judgment, supra, para (447)(4)(h). For a further analysis on the Court’s reasons for striking down Section 57 of the Aadhaar Act, see Vrinda Bhandari and Rahul Narayan, “In striking down Section 57, SC has curtailed the function creep and financial future of Aadhaar,” The Wire, Sept. 28, 2018, https://thewire.in/law/in-striking-down-section-57-sc-has-curtailed-the-function-creep-and-financial-future-of-aadhaar. ↑ |

| 27 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 468. ↑ |

| 28 | Section 139AA, Income Tax Act prescribes the mandatory linking of PAN card with the Aadhaar number, thus necessitating Aadhaar for the payment of income tax. ↑ |

| 29 | Sections 4(4)(b)(ii) and 29(3)(a), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 30 | The Supreme Court in the Aadhaar judgment narrowly interpreted the definition of “benefit, subsidy or service” under Section 7 of the Act and thus struck down the notifications making Aadhaar mandatory for school/entrance exams under CBSE/JEE. See Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 379. ↑ |

| 31 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, paras 227-228, 229, 510.2.1. ↑ |

| 32 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 510.4.1, 510.4.2, 510.4.4, 513.3, 513.6. ↑ |

| 33 | Section 33(2), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 34 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 513.4. ↑ |

| 35 | National Research Council in Washington DC Report, “Biometric Recognition: Challenges and Opportunities” (2010). ↑ |

| 36 | Hans Varghese Mathews, “Flaws in the UIDAI Process”, 51(9) Economic and Political Weekly (2016). ↑ |

| 37 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 61.4.2. ↑ |

| 38 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 90. ↑ |

| 39 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, para 61.5. ↑ |

| 40 | Department of Economic Affairs, “Economic Survey 2016-17”, January 2017, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/survey.asp. ↑ |

| 41 | Dalberg, “State of Aadhaar: A People’s Perspective”, 2019, https://stateofaadhaar.in/assets/download/SoA_2019_Report_web.pdf, at 18-19. ↑ |

| 42 | State of Aadhaar, at 15, 18. ↑ |

| 43 | Aadhaar judgment, supra, paras 61.1 - 61.7.4. ↑ |

| 44 | Regulation 4(2)(b), Authentication Regulations. ↑ |

| 45 | UIDAI, “Circular No. 1 of 2018”, January 2018, https://uidai.gov.in/images/resource/UIDAI_Circular_11012018.pdf. ↑ |

| 46 | DBT Mission, “Office Memorandum dated December 19, 2017”, December 2017, https://dbtbharat.gov.in/data/om/Office%20Memorandum_Aadhaar.pdf. ↑ |

| 47 | Section 2(pa) r/w 4(3) r/w 8A of the Aadhaar Act. ↑ |

| 48 | Section 8A(4)(a), Aadhaar Act. ↑ |