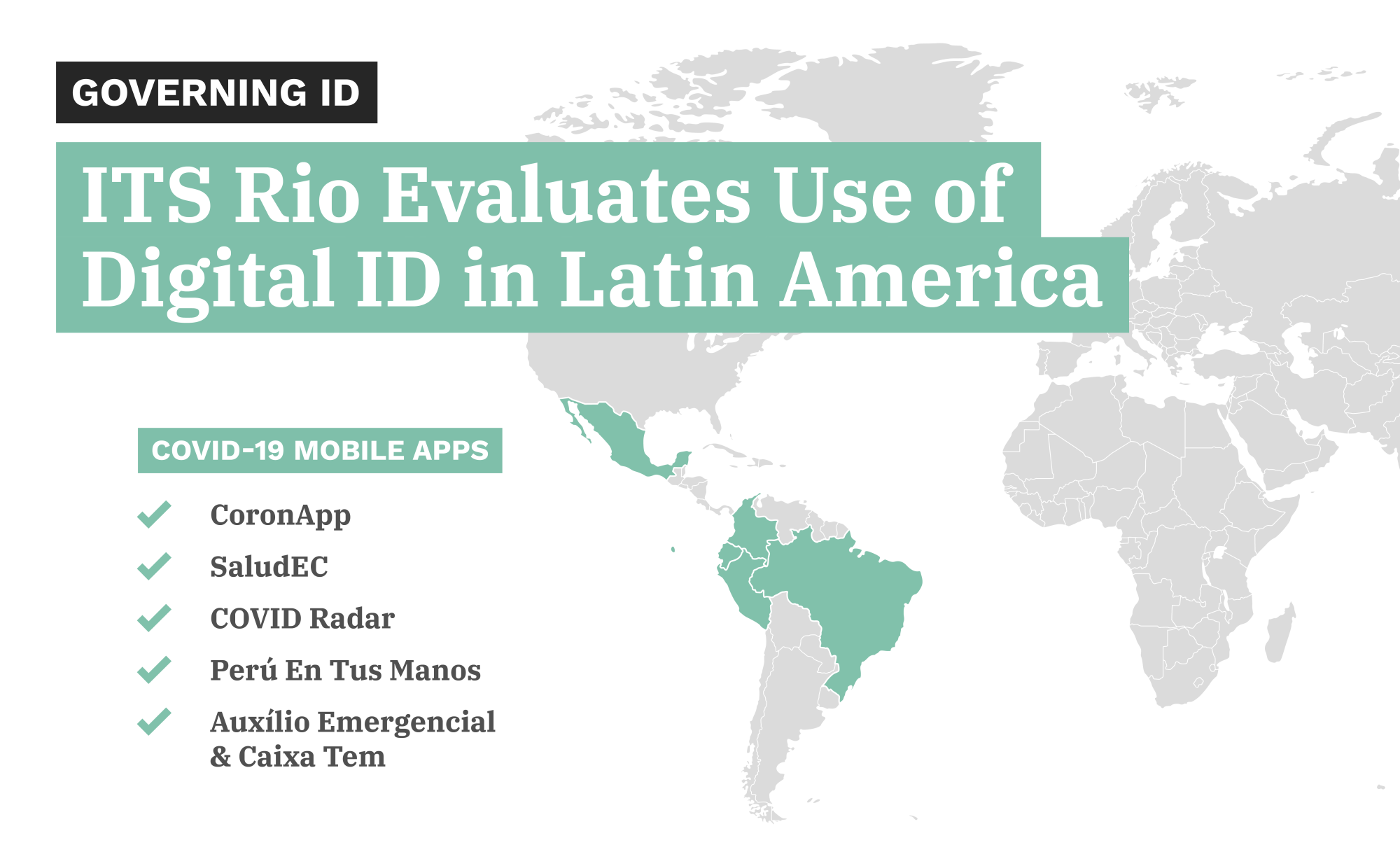

Governing ID: ITS Rio Evaluates Use of Digital ID in Latin America

We are happy to share that the Institute for Technology and Society of Rio de Janeiro (ITS Rio) has adapted our evaluation framework (Centre for Internet and Society’s Governing ID: Principles for Evaluation) to study how digital ID is being used in Latin America as a public health technology response to COVID-19. ITS Rio’s studies look into mobile apps deployed in Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Brazil, and this blog post highlights their findings.

Governments have deployed mobile apps (apps) to manage the spread of COVID-19 and address the impact of the socio economic crisis. The primary objectives of the apps are to (1) conduct contact tracing and (2) monitor spread of COVID-19. For the public, the apps offer guidance on self-diagnoses, fix medical appointments, sound alerts in case of exposure to infected people, etc. Notably, in Brazil’s case, the apps have been built to facilitate transfer of financial benefits. Almost all apps collect personal information such as demographic data, health data, and location data. People are ‘authorised’ to access services and their physical movement is determined based on this data. Such determinations can have far-reaching consequences for individuals and society, well beyond the intended ones.

Hence, it is necessary to evaluate how the apps fare in terms of their legality, respect for human rights, and mitigation of potential risks and harms. The case studies indicate that apps in Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru operate without any specific legislative backing. Overall, there is limited compliance with rights based principles, and no risk analyses or mitigation plans are in place, either. In this respect, Brazil is an outlier — a robust legal mandate exists, and the apps comply with most rights based principles — but it fares just as poorly as the others on risk analysis and mitigation.

In Colombia, users receive free zero-rating internet packs in exchange for registration on the CoronApp app. This has driven low-income sections of the society to register; otherwise user registration remains mandatory only for certain purposes such as conducting self-diagnostic tests. This app does not do contact tracing. Further, there is no reference or adherence to the existing data protection framework, and the app’s terms of use (ToU) do not accurately indicate the specific sensitive data being collected. While the app’s stated mandate is to process data during COVID-19 only, the ToU does not contain any information on destruction or anonymisation of data.

Ecuador provides more functionalities for users such as fixing medical appointments, via the SaludEC app. Registration with a national ID is necessary to use the app, even merely for receiving recommendations and information, which makes it inaccessible to foreigners. The app has been developed by a third-party, who remains the owner and can process the data. Ecuador does not have a data protection framework in place yet. Additionally, the app simultaneously collects users’ geolocation data and provides telemedicine services to users. Collection of such sensitive information carries the risk of being misused to profile users. These concerns are further amplified in the absence of clarity on actors with access to data.

Peru also mandates registration for using the Perú En Tus Manos app. While the app can be used by both citizens and foreigners, a Peruvian mobile number is necessary to register. Sharing geolocation data is also a prerequisite to use the app. This app also gathers geolocation data and offers telemedicine services simultaneously, which can be misused for profiling users.

In Mexico, contact tracing is the primary aim of the COVID Radar app. The app can be used without sharing identity information or registration, and overall is aligned well with international privacy best practices for contact tracing apps. Developed by a private entity, it is now run by the government. There are rules ensuring that the data is not transmitted for commercial purposes, however, precisely which actors (public or private) may have access is not known. Mexico has a data protection framework with a functional regulatory authority.

In Brazil, both Auxílio Emergencial and Caixa Tem apps need to be downloaded to receive welfare payments from the government. One helps users register to determine eligibility for receiving benefits, while the other is for creating an online savings bank account to receive cash transfers. The national taxpayer ID (known as ‘CPF ID’) is necessary for registering on the apps. The apps are run by one of the main state-owned banks in Brazil responsible for welfare payments. Only public sector entities are permitted to use the platform — whose roles are well defined and are subject to data protection laws. Despite these factors, of the 95 million people who applied via the apps, 57 million received benefits, whereas 37 million were denied access and the remaining were placed under review. The denials were on account of poorly maintained identity records by the government, and making the CPF ID mandatory for registration despite poor coverage of CPF ID registries. Further, no risk assessment exercises had been conducted prior to rolling out the apps. The exclusionary impact was compounded due to the apps being accessible and usable only on smartphones. Severely aggrieved by the system, people had to approach the courts, resulting in multiple litigations against the government.