Digital ID in the UK:

Insights from Exploratory Research Mapping

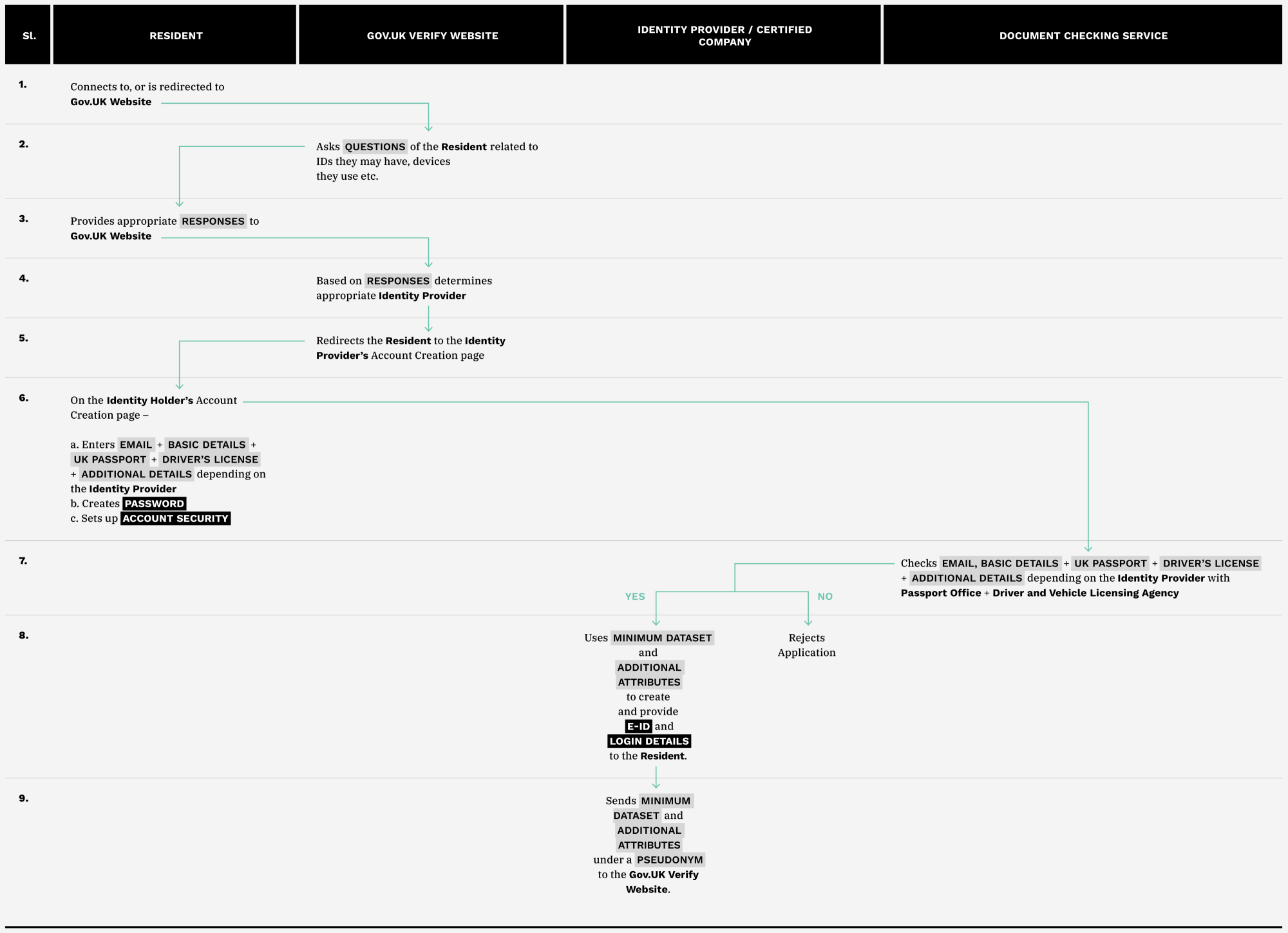

The United Kingdom enables residents to access various government services online through its GOV.UK Verify platform, which was developed by the Government Digital Service (GDS). This system is unique - while most other identification systems involve the government carrying out the process of identification, Verify outsources this process to designated private sector entities who verify residents’ identity by checking against a number of public and private records. This also makes the system federated because residents can choose between a range of commercial identity providers. With the government providing standards for identity verification for different levels of identity assurance, these private identity providers validate residents’ identity and provide them login credentials for authentication. In order to maintain user privacy, identity providers do not know which government service the resident is attempting to access, and the government service does not know which identity provider has been used to verify residents’ identity. Moreover, different government services require varying levels of identity assurance, which allows residents who may not have all the required documentation to access a wider pool of services than if all government services demanded one single high standard of identity assurance.

Insights into a federated ID system

The identification and authentication process maps provide an insight into the functioning of a federated ID structure atypical to most other national systems we have seen. By allowing different identity providers and varying levels of identity assurance, users are allowed the choice of accessing services based on the level of identity assurance they are able to reach. This federated architecture, both of providing identity services and of storing private information, also ensures there is no single point of failure. A central hub or “broker”, attempts to act as a “privacy barrier” between the service provider and the ID provider, mediating the access of identity providers to government services.1 Another advantage that comes with the use of several private identity providers is the presence of redressal mechanisms and customer service in case of technical difficulties; the Verify framework allows ID holders and applicants constant user support, either through their identity provider or directly to the Gov.UK service. There are undeniable drawbacks to a federated structure as well—allowing private identity providers to access and potentially share private information and government records. For instance, in the identification map for Verify, we see that identity providers check details provided by applicants against records of mobile phone providers, credit agencies, HM Passport Office or the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. Although intended to be more accessible to those residents who do not have sufficient government ID, this sharing of information amongst private service providers, even in the presence of rules issued by the government, is alarming.

In the case of the UK, these identity providers are commercial third-parties often without existing trust relationships with UK residents; this differs from the ID structure employed in Canada where banks, which are typically already in trust relationships with customers, and are already privy to a lot of customer private information due to KYC requirements, serve as identity providers. Another problem of this system that the UK is currently facing is a lack of clarity on the consequences of a private identity provider seeking to leave the system, and how the users of that service will continue to use their digital ID. As of now, users of identity providers who have left the platform can access their account until March 2021, after which they will have to shift to one of the two remaining identity providers.

Challenges faced by Verify

Verify can currently be used for a select number of government services, with many more being envisioned. For instance, residents can easily prove their identity to potential employers while applying for a job, enabling the employer to complete the required check of their criminal record before proceeding with the application. However, Verify’s future was hampered by a scathing report from the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) in 2019.2 The report highlighted that less than half of the expected government services signed up to Verify, and fewer than one-sixth of the forecasted users signed up for the ID. It estimated that this was due to errors that made it onerous for users to access services through Verify. These issues usually arise during the process of identification, where residents are sometimes unable to verify themselves because they don’t have the required documents, or occasionally even despite submitting the correct documents. GDS was also unable to design a product that services wanted to leverage, in turn leading Verify to an uncertain future after their public funding stops in 2020. Perhaps due to this, five of the seven original identity providers have stopped providing services to Verify, now leaving only Digidentity and Post Office for residents to choose from.3 Although easy access to Universal Credit was championed as an important benefit of Verify, it was found that only 38% of Universal Credit claimants can successfully use Verify to access it, as they lack the required documents. Universal credit applicants are typically the most vulnerable persons, and the unsuitability of the Verify platform for their necessities was highlighted as a key failure of GDS.

Note: The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an unprecedented surge in demand for Verify, and resulting delays in identification. This has had significant exclusionary impacts, particularly for Universal Credit claimants facing salary cuts and unemployment. To address this bottleneck, the government has provided an alternative means of identification via its Government Gateway, that enables identification for those who may not have sufficient documentation by providing details that only they would have access to, such as their passport or payslips, or even without these documents. In addition, all identity providers provide user support 7 days a week, and Gov.UK provides a support form for complaints. However, there continued to be many complaints of delays in registering and accessing emergency benefits. We see that while the government has been able to mitigate issues of accessibility for those who might not have computer or internet access (by providing telephonic help or physical submission of documents for access to services in these cases), it has been unable to adequately ramp up its system to address demand during an emergency.

Notes

| 1 | There has been some concern about this centralised hub being an additional risk, since in practice the Government could record and access this transaction data. ↑ |

| 2 | “Accessing public services through the Government’s Verify digital system”, Publications and Records, Parliament.UK, last accessed October 11, 2020 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/1748/174802.htm. ↑ |

| 3 | Sam Trendall, “What next for GOV.UK Verify?”, Public Technology, May 15, 2020, https://www.publictechnology.net/articles/features/what-next-govuk-verify. ↑ |